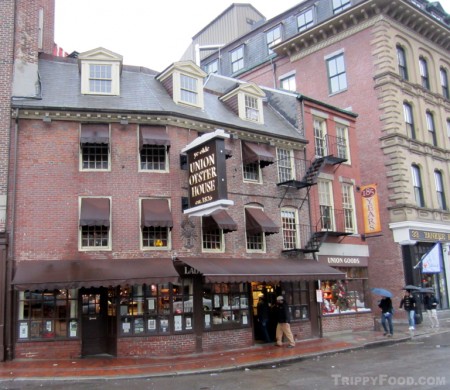

Oldest Restaurant in the U.S.

Union Oyster House, Boston, Massachusetts

Boston, Massachusetts is a city rich with history, including laying claim to being the birthplace of the American Revolution; the signal to riders to warn of British occupation, the Boston Tea Party and the Boston Massacre all took place in Boston and culminated in America’s independence. Millions of visitors to Boston walk The Freedom Trail (the red brick line that winds from Boston Common to the U.S.S. Constitution in Charlestown’s Navy Yards) in order to experience first-hand historic sites with ties to the Revolution. As the red brick road traverses Union Street between Faneuil Hall and Paul Revere’s house in the North End, it briefly passes at the doorstep of a site with its own historical significance: The Union Oyster House. The building that houses America’s oldest restaurant was standing in its current location well before the start of the revolution in the 1770s but didn’t serve as a restaurant until 1826.

It’s difficult to say how many famous historical figures passed through Union Oyster House’s tiny wooden doors – perhaps Alexander Graham Bell called ahead with his order from his nearby workshop; Oliver Wendell Holmes may have judged their filet of sole strictly on its own merit. For certain Daniel Webster had a regular place at the original wooden oyster bar where fresh shellfish is shucked on demand; his meal of choice consisted of multiple servings of a half dozen oysters washed down with a brandy and water. The Kennedys were also known to frequent the restaurant – John F. preferred a quiet booth on the second floor that now is officially designated as “The Kennedy Booth”.

Over the years the restaurant expanded up through the upper floors and into the adjacent property – the staff is more than happy to entertain your desire to have a look around, but with all the interconnected rooms that make you feel like you’re making your way through a sea shanty mansion you might want to leave a trail of oyster crackers to find your way back. Each area of the restaurant has its own unique, historic charm, including the rooms on the upper floors (complete with fireplaces and seriously antique furnishings) that truly make you feel as if you’re dining in a colonial home.

If you don’t manage to score The Kennedy Booth, or you’re traveling on your own, consider plunking yourself down at the oyster bar just inside the front entrance – it’s probably the most entertaining area in the restaurant. For starters, the bar area is backed by Union Oyster House’s front street-level windows, meaning you’re likely to see the faces of dozens of Freedom Trail hikers peering in to catch a glimpse of the seafood on ice. Shellfish that arrives daily is shucked at the same wooden half-circle bar where the honorable Mr. Webster got his oyster on; for authenticity and freshness I recommend getting the local mollusks – on my visit I asked for a half dozen of local oysters, and although I couldn’t tell the difference between the Wellfleet and Cape Cod oysters by the shell, taste was another story. The shuckers on duty looked like they stepped right out of a Herman Melville novel, and although they were friendly and informative, they didn’t mess around when it came to the oysters. Armed with oyster knives that looked like prison shanks, the shuckers force the blade in between what is presumably the oyster’s hind quarters and then with a pile-driving blow, smash the handle into a stone block that quite possibly started its life as one of the cobblestones that pave Marshall Street outside.

The oyster bar is lined with everything you might possibly wish to disguise the taste of the oyster with – lemons, horseradish, cocktail sauce, Tabasco – but you’ll never be able to judge the quality of the shellfish unless you savor them au naturel. The Wellfleets had a sweeter taste than the Cape Cod, but the latter seemed to have firmer, meatier “flesh”; both had ample enough amounts of chilled brine to recall their cold aquatic origins; neither had the slightest funky ammonia smell or taste present with poor quality seafood. The Grail Knights would have smiled upon me with great favor knowing that I chose wisely.

I’m somewhat on the fence about the clam chowder – while the soup was laden with thick, tender chunks of clam meat and perfectly cooked potato cubes it was also obvious that they used a thickener (such as flour or corn starch). While chowder purists will argue that sans thickener you’re dealing with clam soup, I prefer it on the thinner side. The chowder was still hot and delicious, creamy and satisfying and as good a bowl as you’d expect to find anywhere in New England. Garnishing your chowder can get out of hand, and if your modus operandi results in a bowl of “chowdah with buttah, black peppah and some oystah crackahs”, well, the oyster bar has you covered there as well.

Choosing a restaurant by location can be a disappointment – canyon views, revolving towers and “boat in” establishments do not always equate with quality food at a moderate cost, but at Union Oyster House the sense of history does not overshadow the cuisine. I try not to miss the Union Oyster House each time I return to Boston – it’s a memorable experience from the first sip of Samuel Adams to putting your John Hancock on the bill.

Union Oyster House

41 Union St

Boston, MA 02108

GPS Coordinates: 42°21’40.45″N 71° 3’25.10″W